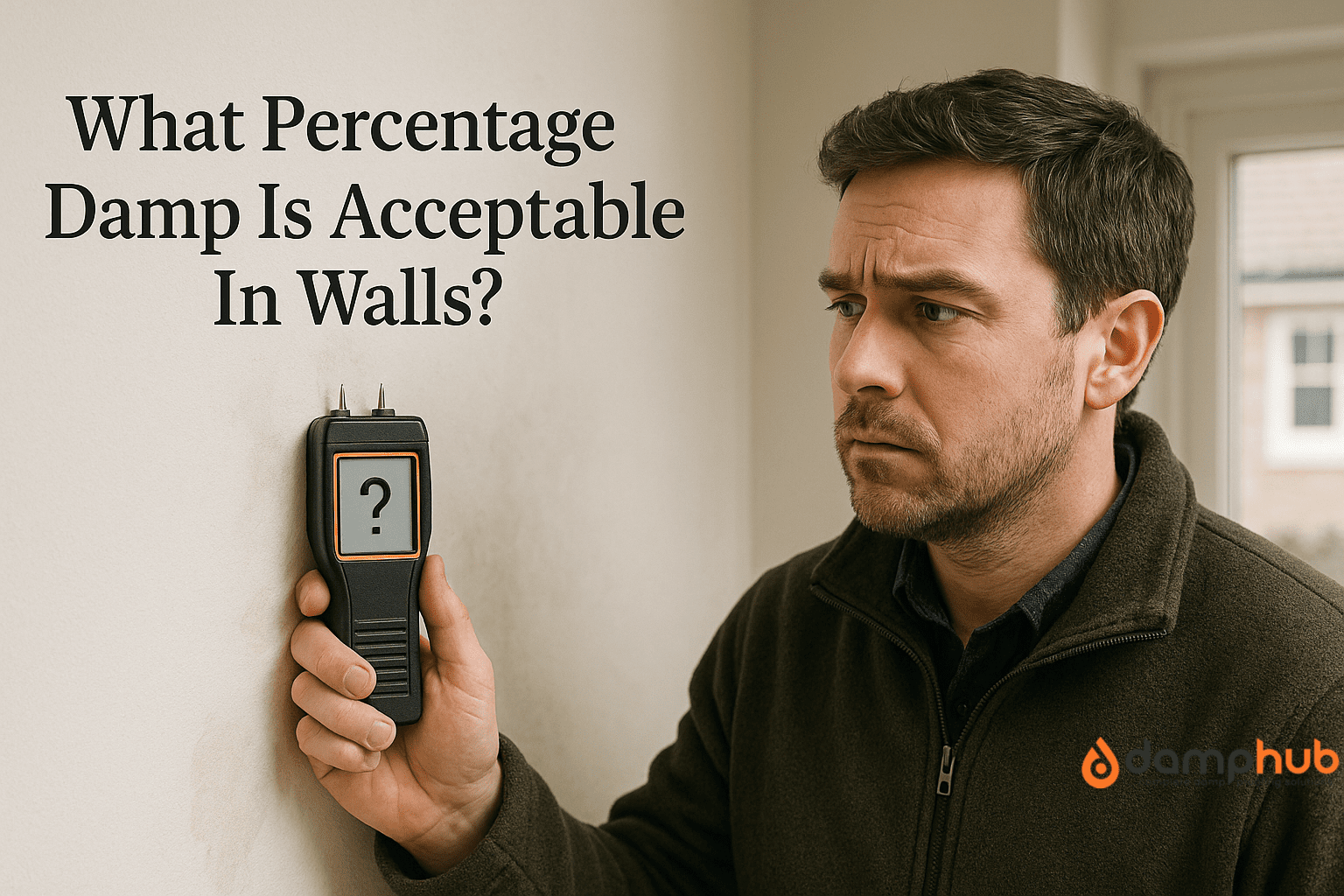

You’ve just had a damp survey done. The surveyor points a moisture meter at your wall, frowns slightly, and says, “It’s reading around 18%.” Now you’re wondering… is that good? Bad? Should you panic? Or is your wall just being a wall?

The exact question you want answered is “what percentage damp is acceptable in wall?

The truth is, there’s no one-size-fits-all number. But there are clear warning signs, acceptable ranges, and things you absolutely should not ignore.

Let’s break it down—plain and simple.

What Does “Percentage Damp” Actually Mean?

When someone says your wall is “15% damp,” they’re usually talking about how much moisture is present in the material. Most damp surveyors use a handheld moisture meter, press it against the wall, and get a reading in seconds.

But—and this is important—those readings aren’t always 100% accurate.

There are two types of meters commonly used:

- Protimeter (pin-type): Measures electrical resistance between two pins. The more water, the easier the current flows.

- Surface scanners (non-invasive): Measure moisture close to the surface, using radio waves or capacitance.

Each gives readings as a Wood Moisture Equivalent (WME)—basically, how damp the material is compared to wood.

So… What Percentage Damp Is Acceptable?

Here’s a quick cheat sheet:

| Moisture Reading (WME) | What It Means |

| 0–15% | Normal – typically dry. No concern. |

| 16–19% | Borderline – could be drying out, or might be early-stage damp. Monitor. |

| 20–24% | Damp – further investigation needed. Something is likely causing moisture buildup. |

| 25% and above | Wet – this is a red flag. Active damp is likely. Needs attention. |

Note: 👉 These numbers apply to masonry, not timber. Timber has different thresholds.

But Wait—It Also Depends on the Wall Type

A 17% reading in a modern plasterboard wall might not be a concern. But in an old solid brick wall? That’s a different story.

Here’s why wall type matters:

- Solid walls (pre-1920s): More prone to moisture because there’s no cavity to stop water from moving inside.

- Cavity walls (post-1930s): Built with a gap between the inner and outer wall leaf to reduce moisture penetration.

- Rendered walls: If the render cracks or traps moisture, the readings can spike—sometimes from trapped condensation, not ingress.

- Plasterboard: Soaks up moisture quickly but also dries fast. High readings here can come from a single leaky bath or steamy room.

👉 Must Read: What is Damp – A Complete Guide

When Should You Worry About a Damp Reading?

Let’s say your survey shows:

- Upstairs bedroom wall: 18%

- Downstairs kitchen corner: 26%

- Behind the sofa on the external wall: 22%

Here’s how to interpret that:

- 18% in a bedroom might just be mild condensation.

- 26% in a kitchen corner? Likely penetrating damp, or a plumbing leak.

- 22% behind a sofa on an external wall? Probably condensation trapped by poor ventilation.

So it’s not just the number—it’s where the number is.

How Do You Get an Accurate Moisture Reading?

Moisture meters are quick, but not gospel. For more accuracy:

- Use both types of meters (pin and pinless).

- Compared to dry areas—test the middle of the room, not just the damp spot.

- Back it up with infrared—thermal imaging can show hidden leaks or cold bridging.

- Drill core sampling—for real accuracy, samples can be lab-tested (used in legal cases or disputes).

Should You Be Concerned About 15%, 20%, or 25%?

Here’s what typically happens at each level:

- Below 15%: Dry. No action needed.

- 16–19%: Keep an eye on it. It could be drying after the weather or recent work.

- 20–24%: Needs further investigation. Check ventilation, drainage, and any water sources.

- 25%+: This is not normal. Treat it like active damp. Identify and resolve the cause before it gets worse.

What Causes Damp Readings to Go Up?

When finding out what percentage damp is acceptable, you might wonder why damp readings seems too high. There are dozens of possible triggers, but here are the main suspects:

- Rising Damp – Water from the ground moving upward through masonry.

- Penetrating Damp – Rainwater coming through cracks, faulty pointing, or porous bricks.

- Condensation – From cooking, showers, or drying clothes indoors.

- Leaks – From roofs, pipes, radiators, or external plumbing.

- Poor Ventilation – Allows moisture from inside to linger and get trapped in the walls.

- Bridged DPCs – Plaster, soil, or render connecting the damp-proof course and allowing moisture to bypass it.

👉 Must Read: How to Damp Proof a House: 7 Practical Tips from Industry Experts

How Do You Remove Damp from Walls?

Let’s say you’ve tested your walls and found moisture levels that are too high. The big question now is: how do you actually get rid of the damp?

Here’s the short version: it depends on the type of damp you’re dealing with.

Damp isn’t a one-size-fits-all problem — and if you treat the wrong issue, you’ll waste money, time, and probably end up repainting the same patch six months later.

Let’s break it down:

If It’s Rising Damp

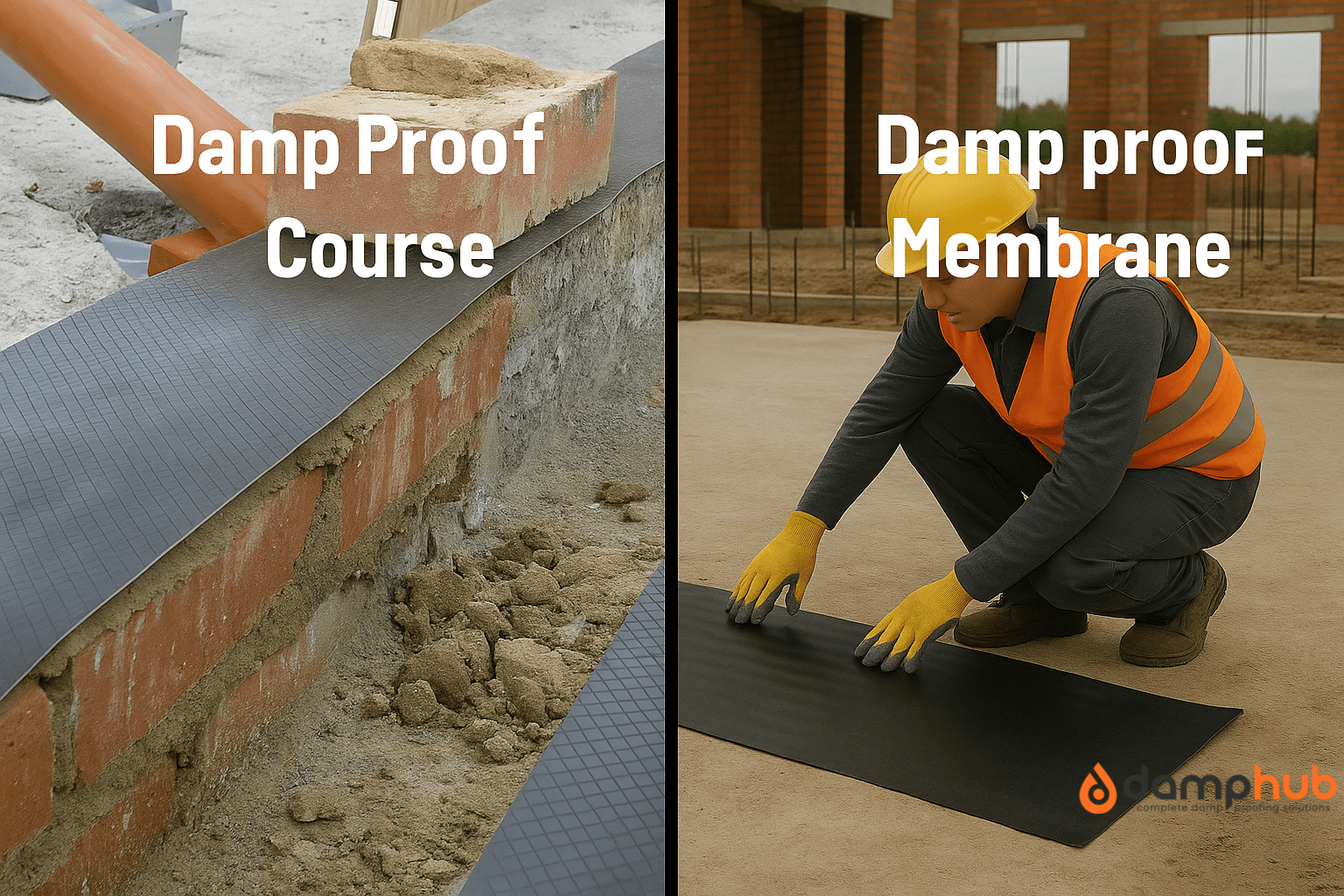

Rising damp comes up from the ground. It usually affects lower parts of the wall, and it’s caused by either a missing or failed damp proof course (DPC).

How to treat it:

- Inject a chemical DPC: This creates a new waterproof barrier in the wall to block future moisture.

- Hack off and replaster: The salt-contaminated plaster needs to go. Use a salt-resistant or renovating plaster on top of the treated wall.

- Check ground levels: External ground or flower beds should sit at least 150mm below your DPC. If not, lower them.

How to Cure Rising Damp in an Old House

If It’s Penetrating Damp

This one’s all about water coming through from the outside — cracks in render, leaking gutters, porous bricks, failed pointing.

How to fix it:

- Stop the source: Fix the cracked render, replace slipped tiles, unblock gutters — whatever’s letting the water in.

- Repoint or seal brickwork: Lime mortar joints that have failed will suck in rainwater. Repointing or applying a breathable water repellent (like Stormdry) helps.

- Let it dry out: Open windows, use a dehumidifier, and don’t rush the redecorating.

If It’s Condensation Damp

This is the most common type — and often the most misunderstood. It’s caused by excess moisture in the air settling on cold surfaces, especially in winter.

How to reduce it:

- Improve ventilation: Use extractor fans in bathrooms and kitchens. Open windows. Install trickle vents if needed.

- Use a dehumidifier: This helps pull excess moisture out of the air, especially in colder months.

- Avoid drying clothes indoors: Unless you have good airflow, this pumps litres of water into the air daily.

- Add insulation: Cold surfaces attract condensation. Improving wall or loft insulation helps reduce the risk.

Can I Just Paint Over It?

You can, but it won’t last. If the wall’s still damp, paint will bubble, peel, or trap moisture — making the damage worse.

Only paint after:

- The source of damp has been fixed

- The wall has dried fully

- You’ve used stain blockers or anti-mould paints (only as finishing layers)

Good to Know

If the wall feels cold and damp, don’t paint it. Even “damp-proof” paints will fail unless the wall is fully dry and the root problem is sorted.

How Long Does It Take for a Wall to Dry After Treatment?

After treating damp (whether rising, penetrating, or from a leak), drying time varies:

| Type of Damp | Typical Drying Time |

| Minor condensation | A few days to a week |

| Leak from plumbing | 1–3 weeks |

| Rising damp (after DPC) | 4–12 weeks (sometimes longer) |

| Flood damage | 1–3 months or more |

Use fans, ventilation, and dehumidifiers to speed things up—but always allow proper drying before replastering or painting.

Final Thoughts: Don’t Panic, Just Investigate

Not all moisture readings are disasters in the making. A slightly high reading could be normal for winter. It could be leftover moisture from decorating. Or yes, it could be a serious problem.

What matters is context, location, and whether it’s getting worse.

If in doubt, speak to a specialist who knows how to interpret the numbers, not just read them.

FAQs

What should the moisture meter reading be for wood?

– For fine woodworking (like cabinets and furniture), aim for 6–8 % moisture content

– For interior wood flooring, 6–9 % is common; substructures are safe up to about 16 % .

– In outdoor or unheated areas, equilibrium moisture content can be 12–14 % .

What is the best waterproofing method for basements?

Interior drainage systems (e.g., French drains with sump pumps) are often the most cost-effective remedy for most homes

For long-term protection, exterior waterproofing, including excavation and applying waterproof membranes, is most reliable, though more expensive and disruptive

A combined approach addressing:

– Drainage (gutters, downspouts)

– Interior sealants (hydraulic cement)

– Exterior membranes and foundation drains

– provides the most comprehensive protection

Can I do damp proofing myself?

DIY is possible for minor issues like condensation or simple damp spots by:

– Improving ventilation

– Applying damp-proof paint or sealants

– Clearing gutters and redirecting downspouts

Major problems (e.g., rising or penetrating damp needing new damp-proof courses) should be handled by professionals

How does moisture get into walls?

Water enters walls through:

– Rising damp – groundwater rising via capillary action

– Penetrating damp – rainwater entering through cracked mortar, missing flashing, or blocked gutters .

– Condensation – moisture vapour from indoor air condensing on cold wall surfaces .

How do you stop moisture from coming through walls?

To prevent wall moisture:

– Install or repair a damp-proof course or membrane

– Ensure proper drainage: slope ground away from walls and maintain gutters/downspouts

– Fill cracks with hydraulic cement and use waterproof coatings or membranes on walls

How do I permanently fix damp walls?

Effective permanent repair involves:

– Identifying moisture source (rising, penetrating, or condensation)

– Addressing the root cause: install/repair DPC, redirect water, fix guttering, add drainage systems, or improve ventilation.

– Repair and treat the wall: inject damp-proof cream, replace plaster (if needed), then apply waterproof seal or interior lining .